Agricultural Carbon Markets

Agricultural carbon markets may offer farmers a unique opportunity to capitalize on sustainable practices, potentially generating additional revenue by selling carbon credits earned through reduced emissions or carbon sequestration. Participation can incentivize adoption of regenerative agriculture methods, enhancing soil health, biodiversity, and ecosystem services. However, farmers must also navigate potential risks, including fluctuating carbon prices, complex market regulations, and contractual obligations that may limit land use flexibility. By understanding these opportunities and challenges, interested farmers can make informed decisions about participating in agricultural carbon markets, balancing economic benefits with environmental and operational considerations. This guide provides a brief overview of the carbon market space to prepare those interested in further conversations with carbon industry representatives.

Carbon Markets:

An emerging opportunity for Nebraska corn farmers

If we could only find a way to trap carbon gas—to capture it and keep it out of the atmosphere.

There is a way, and it’s creating a potential revenue opportunity for corn farmers. By capturing carbon in the soil through practices like reduced tillage, cover crops and nutrient management, farmers may be compensated for helping other entities offset their carbon gas emissions (carbon offsetting) or provide a low emissions feedstock for the many companies actively working to reduce their supply chain’s environmental impact (carbon insetting).

Farmers are uniquely positioned to provide a solution to the many companies, countries and organizations focused on decarbonization — and potentially earn revenue doing so. Carbon markets are poised for dramatic growth, so it’s important that farmers understand this developing market opportunity and be aware of potential positives and watchouts. (1)

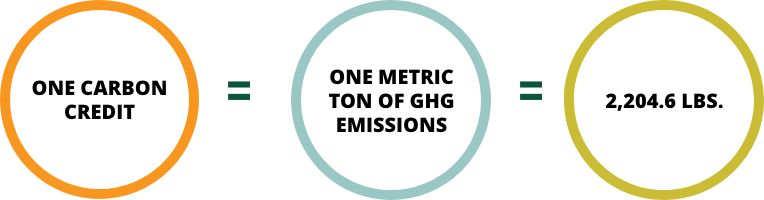

Within a carbon market, carbon is traded or sold as a “credit”. One carbon credit is equivalent to one metric ton of greenhouse gas emissions. That is equivalent to 2,204.6 pounds (Figure 1).

Terms to Know

Carbon credit equivalent

At this point, all U.S. agricultural carbon markets are voluntary. That means participation is driven by the terms of the program and the value they offer. It also means regulation and oversight are limited. While it’s generally accepted that practices like strip or no till, nitrogen management and cover crop usage sequester carbon, the extent of their impact (and how to measure it) is still being debated. Because this area is still evolving, it is often times referred to as “The Wild West” or “A New Frontier” for agriculture. While these programs could provide a unique opportunity for additional revenue on the farm, farmers should thoroughly vet any carbon program and review its terms with an attorney or trusted advisor BEFORE signing a carbon market contract. (1,2)

How do these practices help to reduce emissions?

Soil holds an incredible amount of carbon. When the soil is disturbed, the trapped carbon is released into the atmosphere. The more disturbance, the greater the carbon loss. Practices including strip till or no-till minimize soil disturbance while reducing fuel usage compared to conventional tillage.

Cover crops or sometimes called companion crop, are planted after the main crop is harvested. The purpose for this crop can be broad. Depending on the goals of the operation, cover crops can be “green” manure, nutrient management, pest control, erosion control, moisture control, or forage for livestock. Having a living crop cover the land for the majority of the year helps to reduce carbon loss and helps to recycle nutrients into the soil instead of losing them to the atmosphere. Cover crops can be an effective tool, but must be intentionally managed for success.

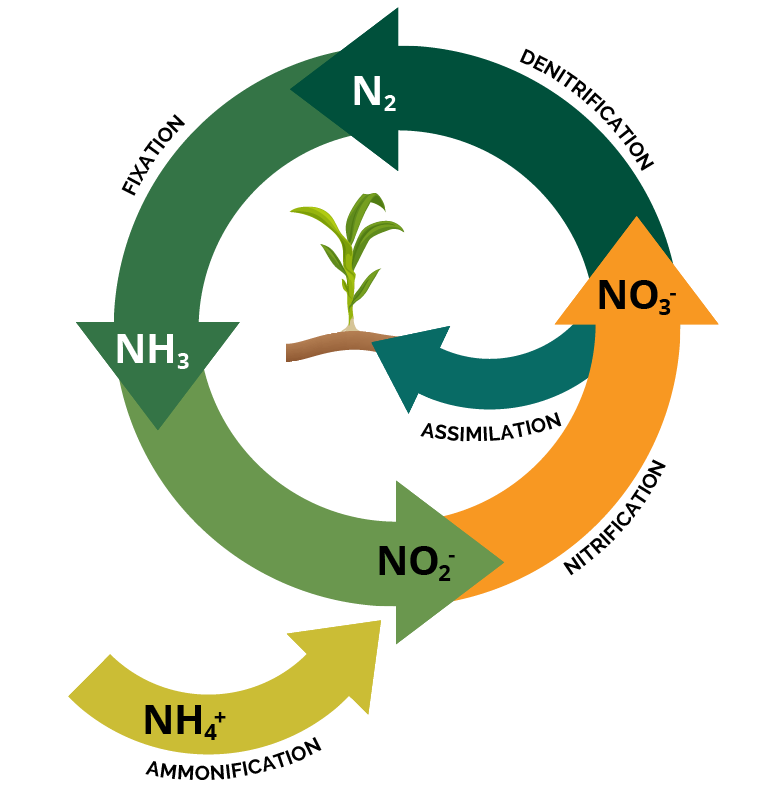

Having a well planned nutrient management strategy can greatly reduce on-farm emissions. Plants can only take up so much at any given time. Any excess is subject to loss from either evaporation, erosion, or leaching. Following the 4R’s of management (Right place, Right amount, Right time, Right form) can minimize on-farm emissions.

How Do Carbon markets Operate?

Carbon markets are where carbon credits or low carbon feedstocks are generated, bought and sold. To enter a carbon market, a producer must work with a carbon company (third party verifier) or carbon program offered by an agriculture industry provider. The producer (seller) will be asked to supply basic on-farm data and eventually must sign a contract and implement the practice(s) outlined within the contract.

A verification process may include additional reporting, soil testing or an on-farm visit to confirm practice change and greenhouse gas reduction. Depending on the program, a producer will be paid either 1) a flat rate for practice change, 2) per ton of carbon stored, or 3) a premium per unit of grain sold. Carbon markets are made up of these key players:

- Farmers, ranchers and landowners (sellers) who implement conservation practices that sequester carbon, thereby creating carbon credits or producing a low carbon feedstock that are sold in a carbon market or sold into a low carbon supply chain.

- Third party verifiers (also called aggregators or verification bodies) facilitate the transaction between buyers and sellers. They ensure quality of data collection, adherence to special accounting rules and proper recording of outcomes.

- Buyers including private companies and/or brokers looking to purchase carbon credits or low carbon feedstocks.

Two Types of Agricultural Carbon Markets: Carbon Offset vs. Carbon Inset

There are two types of carbon markets: carbon offsetting and carbon insetting (Figure 2).

In the case of offsetting, the purchaser of the carbon credits is outside of the agricultural supply chain. A company pays a producer for the “good” they are doing on their farm to store/ reduce carbon emissions so that the company can continue to operate or “emit” the same amount of carbon in their day to day processes. The company is using the carbon credits to “offset” their total emissions. This is where the carbon market space started and to date has largely been slow to catch on within agriculture. Producers by and large have not found the value of payments per tonne of carbon stored worth the cost of implementing low-carbon management practices. Since the inception of carbon offsetting, programs offered within the agricultural industry have begun to alter their strategies to remain competitive with per acre cost-share programs.

In the case of Insetting, the purchaser of carbon credits is within the agricultural supply chain. This system focuses on doing more good rather than doing less bad within a value chain. In this case, a downstream company will pay producers to implement practices that improve and support the longevity of ecosystem services including clean water, soil, air, and wildlife habitat.

Carbon Offsetting

Buyer is outside of the ag industry supply chain (non-ag corporations)

- Farmers are paid for implementing specific practices across their acres.

- Carbon-buying companies pay a fixed rate per acre or per carbon credit. (1 credit = 1 metric ton of C)

- Farmer compensation is based on the amount the carbon offset eventually sells for in the market.

- Contracts can be 1-5+ years.

- Usually limited to new acres of a practice.

Carbon Insetting

Buyer is within the ag industry supply chain (input suppliers, grain buyers, etc.)

Practice-based Programs

- Farmers are paid for implementing specific practices across their acres.

- Contracts are typically 1-3 years

- Farmer compensation is based on the established cost-share rate for a practice change or improvement.

- Usually limited to new acres of a practice, however some programs are beginning to incorporate options for early adopters.

Outcome-based Programs

- Farmers are paid based on the amount of carbon sequestered. How it measures varies from program to program and can include modeling based on agronomic data, satellite imagery, soil testing or a combination.

- Contracts are typically 1-3 years

- Usually limited to new acres of a practice, however some programs are beginning to incorporate options for early adopters.

Carbon’s Role in Agriculture

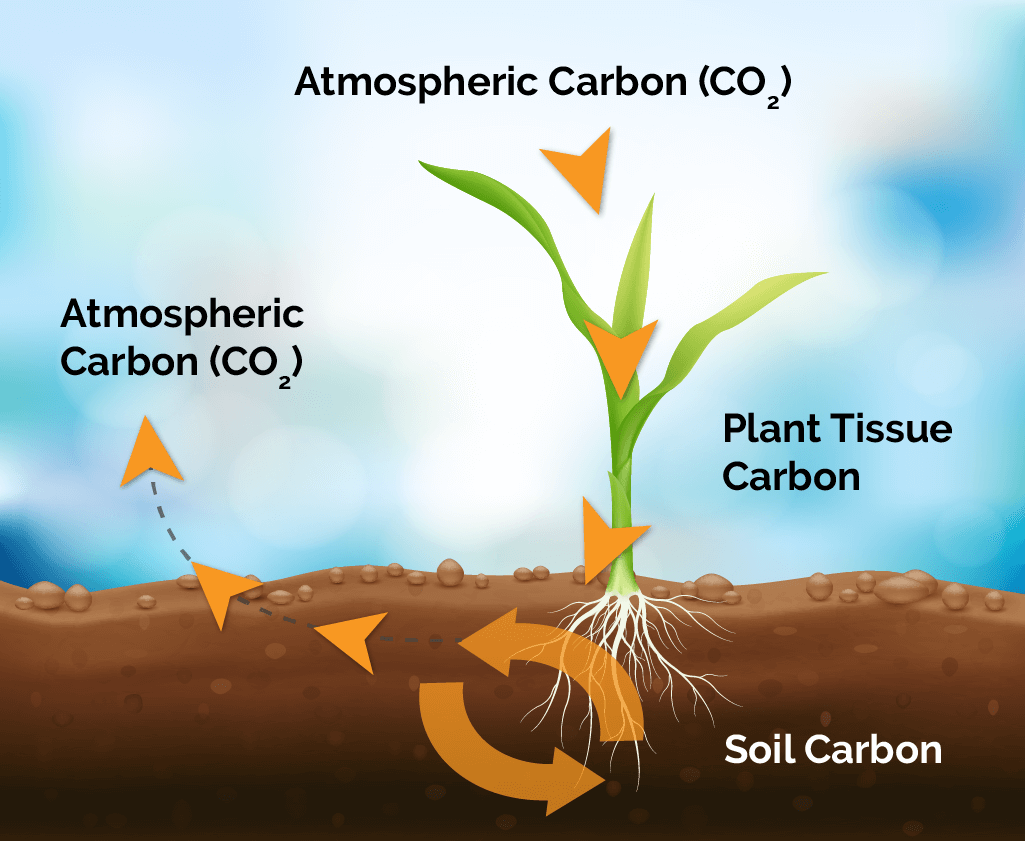

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon is one of the most abundant elements in the universe and a building block for all living things. Carbon circulates through the land, water, atmosphere and living organisms in what’s known as the carbon cycle. Soil organic matter is mainly composed of carbon and is in a constant state of flux. Every year as plant life grows and senesces throughout the growing season, organic matter is added to the soil. While a portion of soil organic carbon is mineralized by soil microorganisms and stored or “sequestered” into the soil, a portion of that carbon returns to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

Land Management Practices as a Carbon Sink or Source

The land management practices we implement to produce a crop have impacts on the carbon cycle and thus, the carbon footprint or “carbon intensity” of an operation’s annual production. The lands’ ability to store carbon is naturally different from place to place, largely due to factors like geology (soil type) and climate. For example, clay-based soils hold more organic matter and can store more carbon than sandier soils. In addition to the natural factors affecting a land areas carbon storage capacity, the combination of management practices used on that landscape can have an immense impact, whether positive (carbon sink) or negative (carbon source).

A carbon sink is an area or ecosystem that absorbs or stores more CO2 than it releases into the atmosphere. Prairies and forests are examples of natural carbon sinks, as the abundant plant life takes up far more carbon in the process of photosynthesis than is released. When we see the implementation of on-farm practices that reduce soil disturbance and maintain consistent ground cover like reduced tillage or cover crops, we see a greater potential for land to store carbon long-term. These practices, among others, have shown to greatly benefit soil health by adding soil organic matter and boosting the activity of micro and macro-organisms within the soil.

A carbon source is an area or ecosystem that releases more carbon than it stores or sequesters. A natural example would be a landscape swept by wildfire. The burning of plant material releases massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. In the same way, the burning of fossil fuels to drive cars, trucks or tractors releases CO2 into the atmosphere. The effectiveness of a single practice, like cover crops, can change depending on the climate, soil type and more. Making agricultural production a carbon sink can look very different from region to region.

Wait, What About the Nitrogen Cycle?

Like carbon, nitrogen also flows through systems continuously and follows the same traits of having natural sinks and sources. Often times nitrogen is left out of the conversation where carbon takes the center stage. Nitrogen though, should not be overlooked. In fact, atmospheric nitrogen (N2O) is 300 times stronger in its global warming potential than CO2. N2O can be released into the atmosphere if it is not utilized by living organisms. That is why producers take great care in following the 4R’s of nutrient management when determining their crop’s nutrient needs.

The Market Is Shifting Toward “Ecosystem Service Markets”

In the last few years, the market has shifted significantly from a place of compliance, where corporations are seeking a swift path to reduced emissions, to a more sustainable supply chain that supports ecosystem services. This space has grown to more than just carbon.

Then

Now

- “Carbon Credit” programs

- Drivers

- International climate/GHG protocols

- Proposed cap and trade system

- Energy policy

- Little impact/longevity

- Carbon ecosystem services markets

- Drivers

- Private sector, supply chain, consumer goods companies

- Corporate social responsibility (people, planet, profit)

Know Your Carbon Intensity Score

Your operation’s Carbon Intensity or CI score is a measure of your operation’s GHG footprint determined by a peer reviewed modeling tool. In other words, a CI score reflects how much GHG’s are emitted into the atmosphere or stored in the ground as a result of annual production. The standard CI score for corn production in the United States is 29.1. When considering an inset or an offset program, it will be important to have an idea of your land’s potential for storing carbon. Many programs require the adoption or improvement of a practice. The amount of carbon storage gained from adopting a practice can vary from one area of the state to the other. If you are considering selling carbon credits, knowing your farm’s carbon storage potential in tonnes of carbon/acre/year will give you a leg up when negotiating terms of a contract.

Carbon/Ecosystem Service Tools

There are several easily accessible tools available for a producer to explore their on-farm environmental impact and/or carbon intensity score. Using basic on-farm data, you can determine where your operation is at in terms of emissions and environmental impact. Keep in mind that these tools are just models or estimations. The true footprint or carbon intensity of your operation will likely vary. This science of measuring on-farm carbon intensity is still evolving and will likely continue to improve through time.

Developed by Nebraska Corn Board

Additional Information on Carbon Markets

Developed by National Corn Growers Association

Developed by Iowa State Extension

Questions to consider before Engaging with a Carbon Program

There are a number of companies participating in the carbon market space including both well-known agribusiness corporations and new start-ups— with more players emerging as this concept gains momentum. Without an official carbon market policy to establish standards, it’s up to the farmers to research the type of programs upon farmers to do some research on the types of programs available, the expertise and experience behind them. As farmers consider options, be sure to be aware of the answers to the following questions:

See also Q&A: Agricultural carbon markets developed by Iowa Corn Promotional Board