The Problem

Petroleum-based plastics are created using a man-made polymer called polyethylene terephthalate (or PET). Unlike other biodegradable materials such as food, or even newspapers, PET does not break down when exposed to the elements.

In the six decades that the PET polymer has been available for mass production, around 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic have been created and subsequently disposed of, mostly via landfills.

The Solution

Perhaps the renewable solution our world requires is being cultivated, grown and manufactured right here in the Cornhusker state!

NatureWorks Engineers a New Market for Nebraska Corn

It all started in 1989. That’s when a group of Cargill analysts set out to identify new uses for plant carbohydrates, such as corn sugar. The research they developed became the foundation for modern-day bioplastics – and the driving force behind NatureWorks as the world’s leading biopolymer producer.

Today, NatureWorks is a leading global biomaterials company that is still part-owned by Cargill, an American agricultural company that caters to a wide variety of markets – including food, animal nutrition, risk management, pharmaceuticals and transportation.

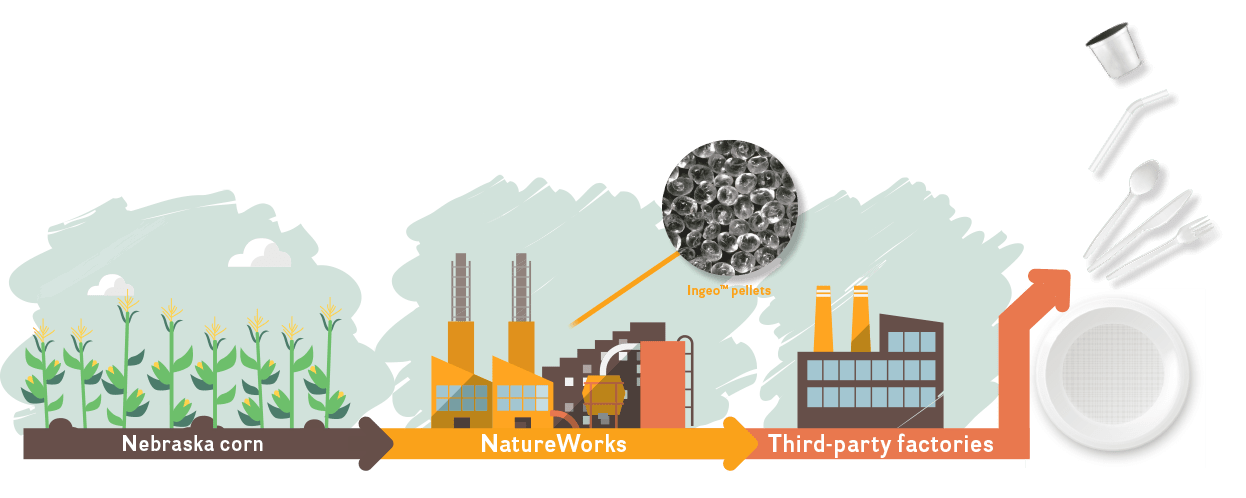

The NatureWorks polylactic acid plant in Blair, Nebraska, was completed in 2003. In 2019, it remains the largest in the world. The Blair plant produces pellets of polylactic acid, or PLA.

The PLA polymer is created using lactic acid that is produced on-site. (Lactic acid is the same chemical that is released in the human body when muscles are fatigued.) After NatureWorks engineers the PLA polymer and manufactures it in pellet form, it is sold using the brand name Ingeo™. But producing an eco-friendly product isn’t the only way NatureWorks aims to improve the environment.

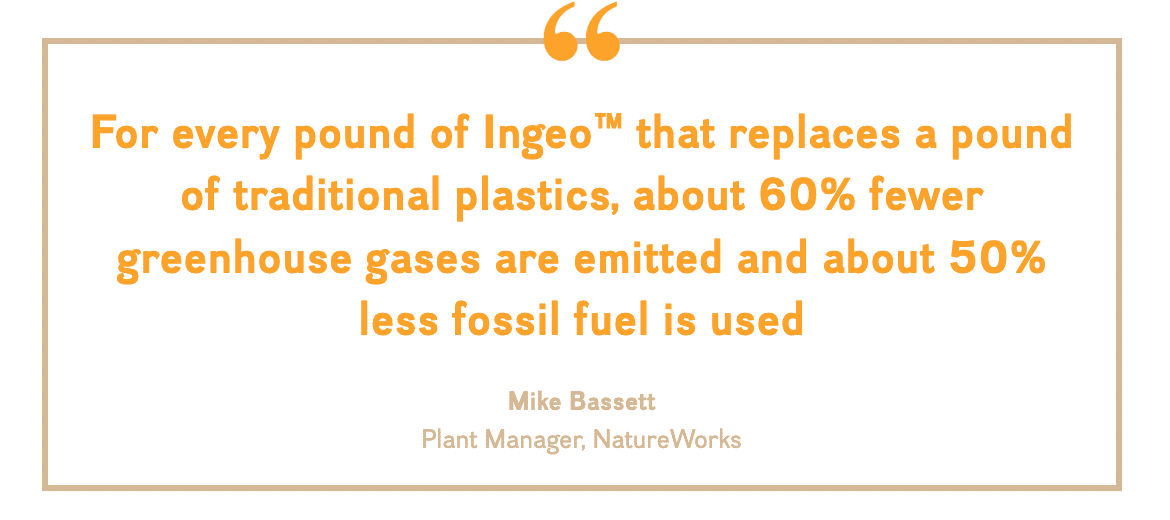

Mike Bassett is the plant manager at the NatureWorks facility in Blair. Bassett said by sourcing its corn close to the plant, NatureWorks uses 70% less fossil fuel and cuts its environmental footprint in half.

Using bioplastics instead of the traditional petroleum-based plastics isn’t a huge change on the production line for most manufacturers. Typically, making the change only requires adjusting the temperature or time it takes to run their machines.

According to Bassett, the most challenging part of getting partners to adopt Ingeo™ is the lengthy approval processes to which companies must subject their bioplastic prototypes.

“After they make the piece of whatever it is – maybe a yogurt cup,” he said, “they have to get that approved. And that sometimes can take six months to a year, depending on the location.”

Ingeo™ can be made into just about anything that traditionally uses petroleum-based plastics, said Bassett. For example, one priority the company is focusing on right now is compostable coffee capsules, like K-cups. Most desktop-style 3-D printers already print with Ingeo™, he said, because it’s very easy to use.

From building a new market for Nebraska corn farmers, to identifying ways for the globe’s greenhouse gases to be used and reduced, NatureWorks’ fleet of scientific innovators is just getting started.